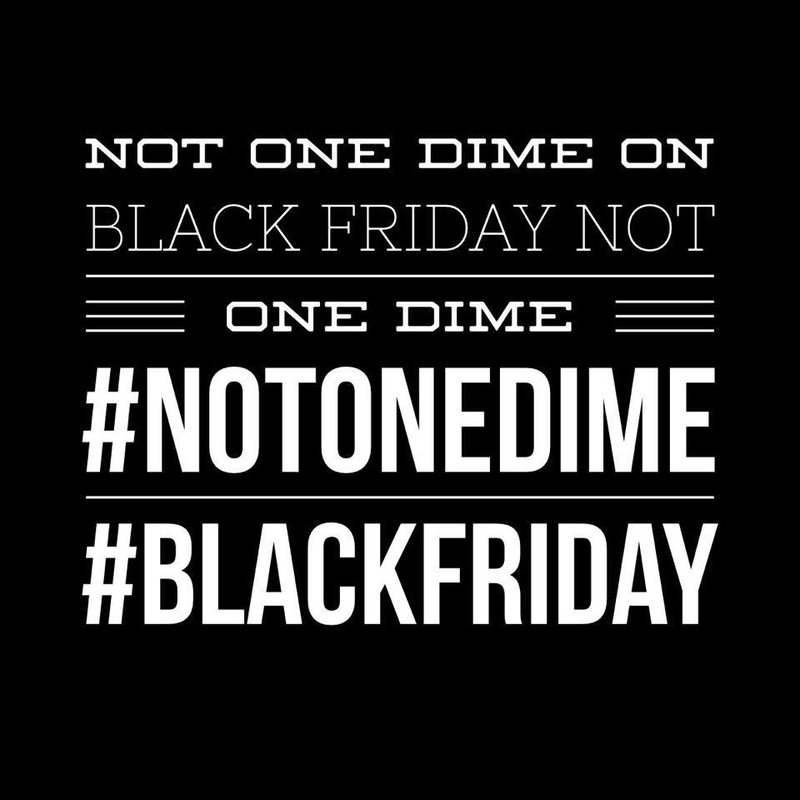

There are 14,297 black people who live in Ferguson, MO. Since Monday, November 24, 2014, approximately 119 people have been arrested. Of that number a little over half were residents of Ferguson AND all of those arrested were not black. White people have gone to jail for what they believe is a travesty to all this country stands for. So have Latinos. And Asians. And Muslims. And Christians. And every group one can imagine. This is not a black issue. This is a human issue. Furthermore, the majority of those arrests did not involve violent crimes or vandalism. Only seven, SEVEN, were arrested on felony charges; the MAJORITY were arrested because of failure to disburse. So, to those who are trying to imply all or most of the black folks in Ferguson are going crazy looting and committing violent acts, shut up. Your voice is neither needed or desired. The majority of the people of Ferguson are at home, grieving and mourning the loss of Michael Brown and the loss of their faith in a system that has failed them time and time again. The majority of the people of Ferguson are sitting behind closed doors, holding their children tighter because they fear allowing them to even go check the mail could lead to their death or injury. So, to all of you armchair racist, do your homework before you make incendiary comments about how black folks are conducting themselves right now. Stop being a tool used by a racist media that wants you to believe black folks are out of control. Trust and believe, we are still in control of our emotions and actions and they world should be on a prayerful vigil that it remains that way. If you can't discern fact from fiction, then stay away from the news. You are a danger to your own weak minds, and the weak minds of those who are listening to you. Oh no. I'm. Not. Going. To. Be. Quiet. I am just getting started. If, by chance, you are as outraged at what took place in Ferguson, MO as I am, then please, join me this Friday, this Black Friday, in this national movement to not spend one dime on a system that clearly believes brown doesn't matter. #NotOneDime

0 Comments

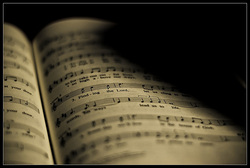

ABC News photo of Michael Brown's parents. ABC News photo of Michael Brown's parents. It is ironic. I am currently reading THE OTHER WES MOORE for school. In a nutshell, the book is about two African American men named Wes Moore who lived blocks from each other. One went on to have a successful career and family life, and the other went on to a life of crime that ultimately ended him up in prison. The moral of the story is you can have two guys with the same name from the same place, yet something simple can cause their lives to diverge and go a different direction. It is ironic that I am reading this book because today I am thinking about a young man named Michael Brown whose life has ended as a result of a police officer shooting him multiple times and in my family, we have a Michael Brown too. He is my stepson, but I never fear for his life the way I do for my son. Not because I love my son more, but because unlike my stepson, my son has brown skin. My stepson is white, and not once in his life have I worried about him getting shot by the convenience store clerk because he was sagging his pants or looking “angry.” Not once have I worried that a routine traffic stop could result in my white stepson being falsely arrested, or worse, shot dead with little or no regard. Not once have I said to my white son, “Smile. Don’t be mean-mugging. Let people know you aren’t a threat.” Not once. The media has decided to focus on the looting and violence that took place after the murder of Michael Brown. Two issues that need to be kept separate. The looters need to be dealt with according to the letter of the law. But the murder of Michael Brown needs to be dealt with separate and apart from this looting and violence, because when we try and connect the two, the message is clear. “See, those folks are nothing but criminals and thugs. THEY don’t deserve justice.” That is the message that is being sent and that is the message that is being heard and regurgitated by so many. If the looters burn down the entire city, that doesn’t change the fact that a mother and father lost their child. My students and I will be talking about this issue. My students are mainly white, but they need to know that this issue is not a black/brown issue. This issue is OUR issue and it will take ALL of us to reach a solution. This issue of police brutality and disregard for certain segments of the population has to be addressed as an issue that is important for ALL citizens of this country.  "One approximation of the annual number of homeless in America is from a study by the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, which estimates between 2.3 and 3.5 million people experience homelessness." ("Facts and Figures: The Homeless PBS.org) Yes, we are our brother's keeper. We are morally responsible for acknowledging and doing something about the suffering of those who, for whatever reason, are drowning right around us. Sometimes it is enough to simply stop and have a conversation. To say, "Hello. Have a good day." To acknowledge that the individual who is begging for your money and/or your attention could just as easily be you or someone you love. So, to all who read these words, Be blessed, and remember, today you might be on top of the world. Tomorrow the world might be on top of you. To The Homeless Guy On The Side Of The Road I try not to make eye contact with you because if our eyes were to meet, I might actually see inside your soul. And the thought of being that close to the essence of you scares me, so each and every time I turn away or I simply focus on the words you’ve written on your sign. Before, your sign said, “Help! I’m homeless,” and before that “I’m hungry. Can you spare some change?” Now, your sign simply says “God Bless.” You ask for nothing—you simply shuffle around in some bizarre dance, arms flapping like a strangled bird. Each day you and your sign haunt me. I worry that if I see your eyes, if I really look into them I will find that you are no con man, no flim flam artist but a man whose down on his luck and has no greater wish than to make me smile and send God’s blessings my way—and for that, you neither want nor desire for me to pay. The other reason I never meet your eyes is because I don’t want to see that you need more from me than some nickels and dimes. I’m worried that to see your soul I’ll see a reflection of the souls of my dad, my uncles, my brothers or my cousins who by fates chance never ended up on the side of the road hoping God or some kind lady would offer them a look—a glance. So I don’t look at you because I don’t have time to be my brother’s keeper. Not today. I’ve got schedules to keep and deadlines to meet and for me to take on your problems on top of my own is way too much. So I look away. I look away. © Angela Jackson-Brown Read more by Angela Jackon-Brown: Drinking From A Bitter Cup  Sometimes, trying to push out the words of a new story or poem is just like trying to push out a newborn. The words get stubborn and comfortable inside the mind where they've been gestating for days, weeks, months, sometimes years. They cling onto the notion that they are safer if they stay wrapped up inside the uterus of the writer's mind. So, sometimes we writers need a literary midwife or two or three to coach us and coax that baby out. Somebody who'll stay with us and that story 'til the birthing process is done. Somebody who'll say, "Daughter, let those words go. Ain't you tired of carrying that full-term baby around in your belly? You are? Then bear down, baby. Bear down and push that baby out." I am in the wonderful, scary space of completing my second novel. The bearing down and pushing out of the words has, at times, been difficult, but thankfully, I have a village of literary midwives who are constantly encouraging me and pushing me to birth this baby out. So, today, I honor them. They know who they are. Love.  Our sons are imploding on themselves. Across all ethnic and social groups, these young men-children are imploding AND WE ARE STANDING AROUND WATCHING AS IF THIS MESS WAS A QUENTIN TERANTINO MOVIE AND NOT REAL LIFE. If we are waiting for "the government" to "change" things, we are fighting a losing battle. The village needs to rise up again. The young men are sending us all of the signals we need that they are drowning and we are standing around with life vests in our hands WATCHING THE TIDE TAKE THEM OVER. PARENTS/TEACHERS/COUNSELORS/COACHES/MENTORS: If you parent/mentor/teach a man-child who is a loner, spends hours playing video games, watches hours of violent television/movies, suffers from manic depression, is bullied, is fascinated by weapons (guns, knives, etc.), doesn't talk to you or anyone, spends hours developing his on-screen persona, THREATENS TO TAKE HIS LIFE OR OTHERS ---THESE ARE RED FLAGS. I'm not saying every young man who fits the descriptions above is a killer in training, but I am saying THOSE ARE SIGNS. If my son suddenly had trouble breathing, that's a sign something is wrong. I'm not waiting to see if something else goes wrong with him, all I need is ONE SIGN and I am investigating with all of the power my body and mind possesses. We will miss signs. We're human. But when the signs are FLASHING in our eyes, blinding us, how can we continue to ignore them? WE DON'T NEED LEGISLATION TO FIGURE OUT OUR YOUNG MEN ARE DROWNING! THE VILLAGE NEEDS TO RISE UP AND RECLAIM OUR YOUNG MEN AGAIN. I don't wait for the young men I teach to "come to me" if they have a problem anymore. I look for the signs, and I pounce. I don't have that kind of luxury to wait for them to realize they are drowning anymore because these men-children are not waiting on us anymore. They are crying out and acting out in ways that brings closure to the lives of others as well as their own. While I wait, my classroom could easily turn into a blood bath. We see it on television every week, sometimes every day. I can't wait for my leaders to lead us out of this wilderness. I love living too much, and I love seeing life radiating on the faces of my students way too much to wait for my government or my employer or anyone else to FIX THE PROBLEM with band-aids and duct tape. And the overwhelming feeling I experience every day I walk into the classroom is, even with all of the precautions I take for myself and my students, we are still at risk. We are still on the frontlines with nothing but slingshots made out of useless rhetoric spoken by politicians and news people who don't even have a clue. On average, I am responsible for 90+ students every semester. I am responsible for making sure that 180 +/- parents get to hold their child again after the semester is over. The days of throwing signals and hints to them to "share with me" if they are struggling has passed. While I'm waiting for them to get brave enough to approach me, I and my students could all be dead and gone. If I can see with my natural eyes that I have students, particularly male students--no matter the hue of their skins--who are coming apart at the seams, I run not walk to them, and engage them in nonjudgmental conversation. I give them my phone number if I see they are without a support system. I tell them, call me and I will not judge you. I encourage them to get counseling. And when necessary, I alert the powers that be that WE have a troubled man-child or girl-child in our village and WE have to do something to help them. WE HAVE TO SEE THEM AGAIN. We have to stop being afraid of gathering them up in our protective wings. We have to stop being afraid of pissing off a teenager or a young adult by getting "in their business." We have to stop trying to be their "friends." That doesn't mean we can't be friendly, but these men-children need authority figures who care and are offering help and solutions more than they need a "buddy." We have to stop waiting for laws and laws and more laws to FIX what is wrong with our men-children. THEY ARE BROKEN. THEY ARE BROKEN. They are broken and no single law alone is going to fix their brokenness. We see them drowning and we do nothing. Gun laws alone will not fix the problem. Mental health laws alone will not fix the problem. Putting warning labels on video games and movies alone will not fix the problem. Parents and teachers and neighbors have to re-engage with our young men. That means, we correct them. We challenge them. We support them. We love them and we DON'T judge them according to their zip codes. We love them because they are a part of our village and our village includes all parts of this country, not just the the dot on the map where we live. WE HAVE TO RE-ENGAGE THE VILLAGE. THE VILLAGE HAS TO RECLAIM OUR MEN-CHILDREN AGAIN BECAUSE RIGHT NOW -- we are losing them.  The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is… Today, I walked into a prison for the first time in my life. I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t know if the women would be hostile. Violent. Mistrusting. Accusatory. Apathetic. I didn’t know. I was excited to be there with them, but I still prepared myself for the worse. I prepared myself to face a room full of angry women who resented my freedom to come and go as I pleased. I imagined a classroom of women shackled and chained by the choices they made that led them to a life of incarceration. I imagined a cross between Orange is the New Black and Shawshank Redemption. I tried to prepare myself for the fact that these women would be nothing like me. Nothing like me. Nothing like me. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is… I looked each woman in the face. Smiling faces. Hopeful faces. Faces similar to the fresh faces I see each time I teach at the University. I heard names like Denise, Angel and Amy. Names that didn’t inspire fear. Names that implied they could have been doctors. Lawyers. Teachers. Names that didn’t convey poor choices. Names that any of us could bear. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is… I saw women with tattoos that mirrored my own. Nothing scary. Just names of babies. Names of boys they thought would love them to infinity and beyond. Images of loved ones gone but not forgotten. Birds. Hearts. Bible Verses. I heard women tell stories similar to my own – stories of abuse, self-loathing, and anger. I saw regret in the eyes of women who knew there would be no do overs. I saw women who, under normal circumstances, would be my colleagues. My next door neighbors. My best friends. My sisters. My aunts. My mothers. I heard women with life sentences speak about dreams for the future. I looked in mirrors and saw me looking back. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is… I saw women whose psyche was sometimes so fragile they hid from the night like it was an abusive lover. I, too, fear the night sometimes. I, too, wonder will that elusive sun really come out tomorrow. I saw graceful movements. I heard lyrical voices. I saw beautiful flowers I wanted to rescue and take home with me so they could stretch towards the light and grow the way they were meant to grow. Only grace and good fortune allowed me to say my good-byes and walk outside into the light, but, before leaving, I promised. I’ll be back. I won’t leave and unremember you. I’ll be back. I promise you, I’ll be back. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is I got lucky. The only thing separating them from me is…  Source: Fun At Zoo Source: Fun At Zoo Shortly after the Fourth of July in 1998, I suffered a stroke. Like most days, I woke up with an excruciating headache, and like most days, I popped a couple of Tylenols and tried to forget about it. However, on this particularly morning, there was no forgetting it. By the end of the day, I was in the intensive care unit of Dale County Hospital in Ozark, AL, unable to move my left side or speak. I was terrified that I might die, or worse (In my mind), lose the ability to think clearly. I also remember thinking, I am 30 years old, and if I died today, what would be the legacy I would leave to my son, Justin? At that point, I was in a marriage that was past the point of needing to end. I had unresolved issues about my childhood. But most of all, I did not believe that I had done anything in the world that would make anyone remember I had ever even been here. At that moment, I promised myself if I survived, I would live every day like it was my last. Some days I’ve fallen short of that goal…by a lot. But all and all, I think I did a pretty good job of at least remembering my goal, even when I didn’t meet it. So here we all are. On the cusp of a brand new year. If you had asked me that summer of 1998 would I still be here almost 16 years later, I probably would have laughed (if I’d had the strength) at the very thought. Mainly because, my prayer that day was simple: “God, just let me live to see my son graduate from high school.” Thankfully, I exceeded that wish. So now, as the world contemplates their New Year’s resolutions, I encourage us all to not worry so much about the things we want to do different in 2014. We have plenty of time for that. Instead, let’s celebrate all of the things we’ve gotten right in 2013. I mean, look. We’re still here. We may have royally messed up from time to time in 2013, but we survived it, and hopefully, we are coming out on the other side stronger and wiser. Let’s vow to leave all negativity in our rear view mirrors. Let’s look back at 2013 as a success because we’ve made it this far, and let’s meet 2014 with a year’s worth of positivity and the mental fortitude to make it the best year ever. Happy New Year Everyone!  Mom and Granddad (I never got to meet him) Mom and Granddad (I never got to meet him) By the time I turned 16 and started looking for my birth mother, I was angry. I was suffering from “mommy abandonment issues” and I wanted to find her so I could punish her. I’m not proud of that fact, but it is the truth. I’m thankful I did not find her then. Emotionally, I was not ready for a relationship to begin between the two of us and I’m afraid, had I found her, things would have quickly fallen apart between us. So I say with gratitude, my journey to find my mother was a slow process with a ton of road blocks in the way. I started my search before there were computers like we know them, so my process involved writing letters and making phone calls. On my adoption papers it said her name was Gwendolyn English and I was born in Montgomery, AL. That’s all I had to go on. For some reason, since I loved English so much as a subject, I just knew she and I were destined to meet one day. In my heart, I knew it was just a matter of time until I found her. But all of my searching seemed to lead towards more and more dead ends, and there were so many monumental events that took place that I wanted her to be there to witness. My high school graduation. My marriage. My graduation from college. My son’s birth. My divorce. My stroke. Yet, it was almost another twenty years after I began my search at age 16 before I found the woman on my birth certificate – Gwendolyn English. I remember walking to her door, anxious, even though she said she couldn’t wait for me to arrive. When she hugged me for the first time in my adult life, I felt like I had come home. My adopted family, especially my daddy, meant everything to me; I was thankful that I grew up a member of the Jackson family. But she was always the missing component. And then I found out that I had siblings, and having grown up an only child, I felt blessed beyond measure. Not to mention all of the fabulous aunts, uncles and cousins I inherited. My life was moving toward completeness. A few months ago, a television show called “I’m Having Their Baby” aired, and it became a source of conversation for the two of us. The show was all about women who made the decision to give up their babies for adoption. One day my birth mom said, while we were discussing the show, “I wish I could talk to those young women and tell them how difficult it is to give up a baby.” Shortly after she said those words, I approached her about doing this interview with me. I think she was a little hesitant at first, but eventually, she and I made the decision to share part of our story. So, here it is. My interview with the woman who birthed me into this world and set me free for just a little while – Gwendolyn English Pendleton. Hi, Mom. Tell me about that first year after the adoption. I didn't handle the first year very well. In fact, I was nearly a basket case. I was determined to keep the adoption a secret, leaving me with no one to talk to, and at the time, I didn’t have God in my life, so I truly felt lost and alone. When I was little, I used to pretend you were a Queen in a far-away kingdom, and one day, you would come and find me. What are some of the dreams you had about me and my whereabouts? In my dreams of you, you were always an adult. I never saw you as a child. And when I did dream of you, I didn’t find you in the dream, you always found me. You were at the front door of the house. I never saw myself taking you from your adopted family. It would have been the wrong thing to do. My dream was seeing my daughter as a young lady, knocking at my front door. And, it almost happened just that way. You mentioned that after you put me up for adoption, you went back looking for me. What was it like for you when you found out I had been adopted? It was sad and then again, it was almost a relief that you had been adopted early and you weren’t stuck in a dreary orphanage, like the ones in the movies about abandoned children. You were such a beautiful baby. I did have some mixed feelings when I found out you had been adopted though. I was happy for you, but I was also disappointed because my deep desire was that I might reclaim you. However, I realized that getting you back would have been a difficult task since I had already signed away my rights. Another part of me decided that my baby was in a good home and I should allow her to grow up there. This decision finally gave me a level of peace. In what ways did the adoption affect your relationship with my sister and brothers? It made a difference when they were older and their father and I divorced. Having given you up, I knew I would not allow another child to get away from me. It made me want to hold on to them more. The adoption, I believe, caused me to be a stronger mom, and a more determined mom who would fight to keep my other children and not let anyone take them out of my arms. Describe what your first thoughts were on that day I called you for the first time. That day you called, I knew who you were before you even said your name, a name that I chose for you – Angela Denise. I knew your voice. It was our voice. And when you said your name I thought, God did just what he said he would. He brought my baby home!! It was a miraculous moment. It was glorious. It was awesome. Because my adoption was a secret to most members of our family, how did you deal with my sudden re-appearance into your lives? I called the family together and told them the truth. They were so wonderful and so understanding. I'll never forget it. I thank God for all my babies and my other family members. You and I have spent the last 13 years trying to get to know each other. What has been some of the challenges? And what has been some of the great moments? We need to be seeing each other more – that’s the challenge. The great moments were the very first time I saw you as a young lady and every time I've seen you since. The challenge has only been the physical distance between us. If you could give advice to mothers contemplating adoption, what advice would you give to them for surviving those years apart from their child? To be honest, I have no advice to give. Every woman must decide for herself what the right decision is for her. Fortunately, I came through by the grace of God. I know that God allows us to go through things for spiritual and mental maturity, even when we bring these things on ourselves. Would I make that decision to give up my baby again? I don't know. I'm not that person anymore. She was only 19 and very confused. I don’t believe I would do it now, knowing what I know. How do I know I wouldn’t give up my daughter – give up you? Because I'm stronger and wiser, and I know that I wouldn't have to go through it alone. Mom, thank you for doing this interview with me. We’ve been through a lot together, both when we were apart and now that we are in each others' lives again. Let me say what I have said before, I have no regrets. I was loved. I was nurtured. I made a difference in the life of my parents who really wanted me. You did the right thing. If you would like more information about adoption, visit the National Council for Adoption website by clicking here. If you would like to read more blog posts by me, visit my blog, “Writing in the Deep” by clicking here. Thank you for visiting my blog. Don't be a stranger.  A note from Angela: I grew up a church girl. It was expected where I came from in Ariton, Alabama. Unless you had a fever of 110 and were too delirious to walk and talk, you were going to be sitting in a pew on Sunday morning, and in the case of my church, Mt. Olive Baptist Church, some Sunday afternoons too. Not to mention Wednesday nights and those long revival meetings during the summer. Oh, I whined about having to sit and listen to our minister go on and on about God and family and community. But really, I didn’t mind, and to be honest, so many of those heartfelt sermons preached by upstanding men and women still live within me today. And anyway, for all of us “church girls and boys,” our church was an extension of home. Going to church every Sunday was like having a weekly family reunion. I got to catch up with my classmates. I got to see my aunts and uncles and cousins. And I got to visit with the Godly women and men who taught me to love everyone – from the person sitting next to me in the pew, to that “wayward sinner” who was one kind word away from becoming a “saint.” I will confess. I have never found what I experienced at my home church all those years ago. And I’ve looked. But I have found a friend who shares similar memories of her time when she too was a “church girl” in a little rural town in Southern Illinois. So, read her story. Even if you’ve never spent a second in church, you would be hard pressed not to feel a sense of longing for the rural American experience she shares in her essay below. Thank you, Lauren, for taking us back to a time that for many of us was as close to idyllic as it gets. The Education of Lauren: One Hymn at a Time by Lauren Bishop-Weidner I remember sitting in “our” pew in the Rosiclare United Methodist Church (third from the front on the right), pretending to be good. I’d fidget in my seat, swing my legs one at a time, then both at once, count ceiling tiles, look out the stained glass windows, annoy my siblings. My sister Joanie and I would play complicated games, hiding our mischief under innocent expressions. We’d write coded notes and stifle our giggles, or see how many words we could make out of the sermon title. I’ve heard that some of God’s little pirates managed to smuggle in books to read, but I never got away with it. My book would be routinely confiscated, and I would have to listen—again—to the tedious lecture about respectful attention in church. One preacher’s son, older than I, openly read comic books, but this did not impact my parents’ judgment—if he jumped off a cliff, would I follow? Eventually, I accepted defeat and turned to the two books that were allowed, the Bible and the hymnal. The hymnal was easier. My first forays into the Methodist songbook involved the faded brown ones, worn on the edges, copyright 1935, with old timey hymns like “Revive Us Again,” “Bringing in the Sheaves,” “Power in the Blood”—hymns with simple tunes, simple harmonies, simple messages. I would thumb through and look for the ones I knew. Sometimes I’d discover to my great surprise that I’d been singing them wrong. “Rescue the parachute, care for the lifeboat” was really “Rescue the perishing, care for the dying;” and “Par, par, par in the blood” had nothing to do with golf. Who knew? Sometime in the mid-1960s, we got new hymnals, bright red, with a lot more stuff in them—new creeds, new rituals, new songs. The “first lines” index in the red hymnal didn’t always include the more common names of hymns, plus I didn’t see those foot-stompin’ melodies I recognized. Another index showed who wrote what, and the sheer number of hymns next to certain names gave a lesson in miniature about poetry, history, music, and the connections among them. Certain names stood out: Fanny J. Crosby, William Bradbury, Charles Wesley, Isaac Watts. Sunday by Sunday I grew up immersed in the liturgy and hymnody of the United Methodist Church. The hymns breathed new life into old Bible stories, cautioned against sin, celebrated salvation, preached social action. The poetry mesmerized me long before my vocabulary caught up, with lofty, ethereal words you don’t hear every day: “mighty fortress;” “healing stream;” “Calvary’s mountain;” “visions of rapture;” “balm in Gilead;” “sore distressed.” Truly, “words with heavenly comfort fraught.” There were exhortations to repent, to give, to share, to help, “touched by the lodestone of thy love.” The poetic words settled into my bones, and thanks to a comprehensive music program in our school, the music did, too. Through the efforts of both classroom teachers and music teachers, I was able to hear the songs in my head as I whiled away the boring sermon time. As my knowledge grew, I put the harmonies in, and despite the fact that I’m not all that musical, I understood how the hymns sounded. By the time I was into harmony-reading, I was also into folk music. The protest era marched across the sound waves accompanied by a motley mix of rockers and troubadours—Dylan, Joan Baez, Peter, Paul and Mary; the Doors, the Stones, Janis Joplin; Sam Cooke, Mahalia Jackson, the Staples. In church, I checked out their inspiration, filed under “Folk Hymns.” There weren’t many, and they were all lumped together: spirituals, Native American songs, immigrant tunes, mountain melodies. Printed in the middle of the bleakest, bloodiest years of the Civil Rights struggle and the protest against the Vietnam War, the red hymnal—and the United Methodist Church—took a quiet stand for justice. Granted, the arrangements of the folk tunes tended to look a lot like those of the Wesley or Watts hymns. Still, their inclusion represented a deliberate statement. The newest update to the United Methodist Hymnal (1989) reflects assiduous attention to retaining what never changes and revising what does. In some hymns, gender-neutral language replaces the now-archaic use of “mankind” and masculine pronouns, changing words and rhythms in ways I’m not sure I like. But I do like the philosophy that says sexist language is wrong. The spirituals and work songs from the African-American tradition are more authentic and harder to sing. There are languages and folksongs from around the globe, giving the casual hymnal reader a multicultural education steeped in the church’s devotion to inclusiveness, a philosophy surely shared by the Jesus who dined with both Nicodemus and Zacchaeus, the Jesus who spoke kindly to loose women and sharply to church leaders. You really can learn a lot from reading the hymnal. Thank you for stopping by and reading Lauren's phenomenal essay. Click here to read more essays by Lauren. Please feel free to leave a comment below for her OR share your own "rural America" life experience. Click here to FOLLOW me on Facebook which will give you easy access to blog posts like Lauren's and information about my upcoming book, Drinking From A Bitter Cup. Again, thank you for visiting my blog. Don't be a stranger. |

Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

Blog Roll

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed